The images displayed here on Jane’s website were chosen to reflect the values of Wales’ most advanced political and cultural change: The Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act of 2015. The images visually connect with themes established in #futuregen her new book, presented here is our visual arts practice seen through the lens of the exciting new Act.

Leaving Art School in 1979 and throughout our professional careers, we have been lucky to be exposed to a wide range of influences and some amazing individuals, like the great German artist Joseph Beuys, whose works with nature, folklore and Germany’s recovery after World War II helped us understand the primacy an artist’s role can play in society: their social agency. Another influence on us, was the work of UK’s Artist Placement Group (APG). This highly experimental and political group were the first to strategically place artists in public organisations on an ‘open brief’. APG’s work helped lay the foundations for what is now known as an artist-in-residence (A.I.R.) scheme, however the ‘open brief’ remains elusive and largely unrealised in current practice. The A.I.R. platform is for us the mainstay of our practice; we are residency artists who emerged into the ‘time- based’ performance art scene in 1979 at the ICA New Contemporaries exhibition in London.

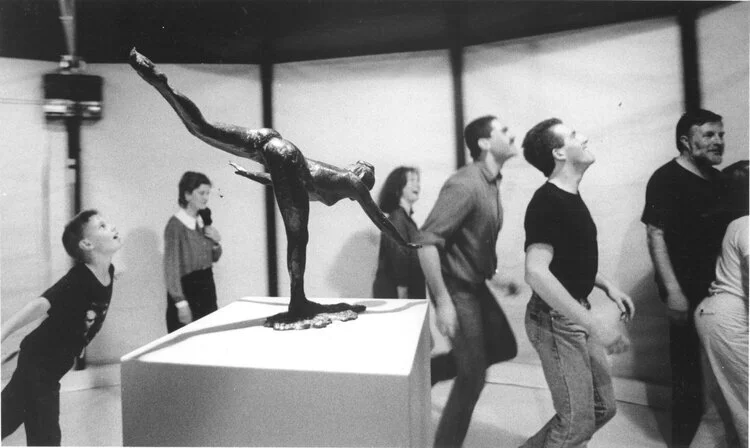

Today, some would say, that Artstation are at the vanguard of Wales's contemporary ‘socially engaged’ artistic movement. When you experience our work, you immediately encounter people caught up in collective activity and social exchange. The interest in conversation in our work arose via contacts we made in Amsterdam during the presentation of our installation Locomotion (1984 Fig 4). We met and worked with cybernetician Professor Gordon Pask throughout a fellowship we were awarded at Amsterdam University in 1988, and in the following year we collaborated with him to present Bitori in Virginia Beach USA. In this period, we learned about ‘Conversation Theory’ (CT), Pask’s formal mathematical description of the minimal construct needed for a conversation and were exposed to a global network of scientists and wonderfully creative thinkers.

These experiences led to new types of language and thinking about ‘conversation’ in the context of our work. We began to use huge rolls of industrial wastepaper and air fans, to make inflatable installations, often at architectural scale, which ‘talked to’ or interceded with places and spaces. As this work developed, it became a way to place people we worked with in conversation, with one another and with more-than-human subjects such as environments, places, situations, materials, sciences, histories, politics, even technologies. Our brand of ‘creative conversation’ with community, developed as a collaborative enterprise, was an exploratory ‘field work’ designed to draw out new understandings and ‘shared concepts’ - a notion directly lifted from CT. Our conversations were sometimes disruptive, challenging perceptions about the way we and other people saw the world.

More recently, we have been attending also to soundscapes, whose ephemeral qualities form exquisite immersive media in which conversations play out. 'Soundscape' is a term defined by Murry F. Schafer in his study of the relationship, mediated through sound, between people and their environment.

In Finding Future’s Way, (2017, Fig 1., Fig 11.) we contrasted the sound inside a beehive to the soundscape of Hong Kong’s city streets, the Bee Hive and the City Hive, bringing an auditory focus to the relationship between humans and the local Asian honeybee. In Riversonics II, (2015, Fig 6) we listened with groups of students to the social and cultural environments surrounding the river Taff, and mapped the life-giving ‘tranquil access’ that the river offers the public.

When social discourse becomes ‘the artwork’ the new aesthetic value and meaning can gain poignancy and relevance to people’s lives, both in community and in organisations, where we might seek an accord with particular objectives or political perspectives. The social matter, of our work constitutes a material which is ‘readymade’1, a Duchampian object even - a conceptual thing, of symbolic and cultural value, which is potentially open to all. Joseph Beuys taught us that ‘everyone is an artist’ and that culture is a ‘primary product’ of human life. The great Welsh writer and philosopher Raymond Williams reminds us that, “real culture is something we all share in”. We try to avoid self-referential or patronising work to spoon-feed needy communities: our role is to catalyse positive change, where we can. The Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin uses the term ‘dialogic’ to describe how conversations, such as those we dare have within community, can extend meaning through a reading of local historical sources that can affect what can be achieved in the future, and how, in turn, these experiences change the way people view their past. It’s known as the ‘Bakhtin Circle’. By implication, the relationships we are exploring through conversations are political, public and dialogic; through them we become aware of the power and control in relationships. Nicolas Bourriaud describes creating art in this way, through social cultural connections and their possibilities, as holding a ‘relational aesthetics’.[2] The (contemporary) artist, he says, comments on the Anthropocene with an archaeological mind in search of the look, feel and meaning of relationships, which are then reflected back as art.

Artstation has always placed collaboration and co-production at its heart. As a company we function like architects bringing together local teams and a professional network of contacts. Together we examine connections and relationships, whose qualities become expressed as ‘relational aesthetics’ through our work.

The issues Artstation addresses through these ways of working, are the following:

Social Contract: human interaction, compassion, salvation, community and the agonised practice.

Environment & politics: inequity, global/local culture, migration, ecology and sound.

Technology: its systems, its immateriality, virtuality, software, and latterly global reach, and

the internet of things.

Originally, we identified as a ‘brand’ name to help distinguish ourselves from other artists of our generation. However, identifying as a company was never about investing in the market of products but about placing our work amongst the mainstream functions of society, not apart from them. Our Art College background provided a rich critique of popular culture and art’s global commodity value. We saw then, as we still do, that monetising art, perverts its real value to community. Markets were a vanity which obscured the creative endeavour of the artist. Conversely, there remains a scarcity of resources for experimental, political or explicitly social art, in the public realm. Until recently, working in community was disparaged by a cultural elite who considered it an irrelevance, some still do. Our political stance has been where possible to de-commodify our works, which remain ephemeral and largely uncollectible (Fig. 8, 13, 15).

Public ideas are slowly changing with regard to investing money in community culture, there remains a suspicion, a scepticism, that ‘they’ just don’t deserve it. The great debacle of Brexit, its divisive undoing of community cohesion, points to this lack of cultural investment in community. 100 years of physical regeneration across South Wales has not touched the ghastly inequity, its corrosive effects.

There are no panaceas that cultural regeneration provides for, but nobody can deny the need to heal the divisions currently dogging our society, wellbeing is perhaps at its lowest ebb for generations. Our project Yellow Brick Road, (YBR, 2015-17) was an attempt at improving the ‘social contract’, by immersing ourselves in the politics and conversation between service providers, civic representatives, landlord and residents, within St Georges Court housing estate in Tredegar. Participatory approaches in contemporary art says Anthony G. Schrag, in his thesis Agonistic Tendencies, are in tension with mainstream art policies and commissioning, and need ‘a new ethical and political understanding of their emancipatory possibilities’. Most interestingly he highlights the role of ‘productive conflict’ in an ‘agonised’ notion at the crux of cultural regeneration/conversation.

Following the pandemic, community life will need to share and renew values which can be ‘owned’ and operated by people themselves, that connect with environment and climate impacts, and help build resilience, a counter to the wasteful polluting economics of excessive consumerism. We proffer our brand of socially engaged art as a way to help to bring social, emotional and intellectual intelligence to the business of healing in community as we emerge out of our homes to socialise again.

That’s all for now folks! If you want to work with an organisation determined to deliver on the new social, cultural, environmental and economic ambitions of the Well-being of Future Generations’ (Wales) Act, please do get in touch with us.

Artstation - Glenn Davidson & Anne Hayes

www.artstation.org.uk

Copyright Artstation 2021.

[1] Marcel Duchamp - Wikipedia defined the readymade art to serve the mind, he utilised the Found object as a rejection of "retinal" art, intended only to please the eye.

[2] Nicolas Bourriaud - Wikipedia defined relational aesthetics as the product of "a set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure as the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space." See also Relational art - Wikipedia